'That's not writing, that's content'

On writing, abundance, and the reduction of culture to content.

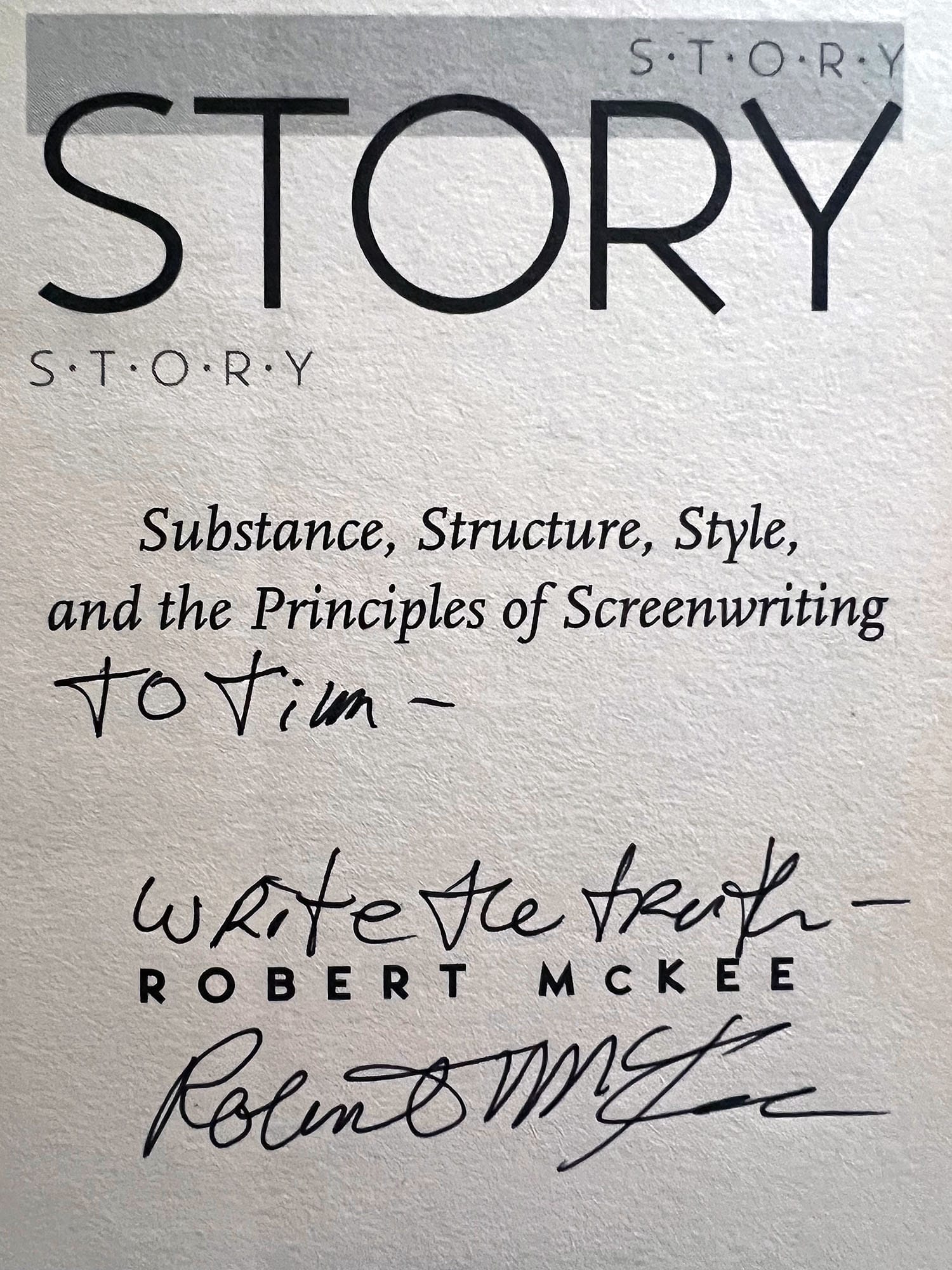

In 1999, I attended Robert McKee's internationally renowned Story Seminar — a three-day exploration of narrative structure, delivered in his dynamic, often acerbic, style.

In the evening glow of the first day, McKee asked how we were doing. In a memorable aside during his discussion of character development, he described the level of commitment it takes to build screenwriting skills, assessing that:

[...] just as it takes a decade or more to make a good doctor or teacher, it takes ten or more years of adult life to find something to say that tens of millions of people want to hear, and ten or more years and often as many screenplays written and unsold to master this demanding craft.[1]

McKee measures this commitment in neglected careers and relationships:

The writer places time, money, and people at risk because his ambition has life-defining force.[1:1]

The strength of an ambition to write can be incomprehensible to those who do not share it.

In her 1998 autobiography, Julie Burchill[2] recalls getting her first typewriter, an ancient model so heavy that her father had to move it around the family home for her.

Burchill relates that:

When I was safely ensconced in my bedroom, banging away through prime time and beyond at all sorts of juvenilia [...], my parents would take it in turns to desert their quiz shows and shit-coms in order to peep around the door and check that I wasn't up to no good. (As if!) 'Doing nice typing?' they'd enquire. Typing. It's a wilful misunderstanding, isn't it? [...] Did they really think that any teenage girl, however dim, got into this sort of state over her w.p.m.?[2:1]

For Burchill, her parents' reduction of her learning to write to 'typing' typified the limited career opportunities on offer to working-class school leavers in 1970s Bristol. These amounted to the uninspiring twin options of 'factory worker' or 'office worker'. Her use of a typewriter, therefore, seemed to signify nothing more to her parents than her development of a purely mechanical skill, perhaps with a view to getting a job in a typing pool. Their 'wilful misunderstanding' of their daughter's enthusiasm stemmed from the perception that typing was a more likely career option than writing.

Burchill's parents' focus on the mechanics of her writing echoes Truman Capote's pejorative epigram directed at peers whose work he disliked: 'That's not writing, that's typing.'

An investigation by the Quote Investigator website uncovers several variants directly attributed to Capote,[3] the earliest from an interview in the Spring-Summer 1957 edition of The Paris Review:

[...] they're not writers. They're typists. Sweaty typists blacking up pounds of bond with formless, eyeless, earless messages.[4]

Capote shifts rhetorical emphasis in this quotation to suggest that the vacuous activity of the targets of his ire is 'blacking up pounds of bond'.

George Orwell[5] applies a similar interpretation when describing the work of the pigs in Animal Farm:

[…] the pigs had to expend enormous labours every day upon mysterious things called 'files', 'reports', 'minutes', and 'memoranda'. These were large sheets of paper which had to be closely covered with writing, and as soon as they were so covered, they were burnt in the furnace. This was of the highest importance for the welfare of the farm […][5:1]

'Typing', 'blacking up pounds of bond', and 'large sheets of paper which had to be closely covered with writing' have a reductive online equivalent in the ubiquitous term 'content'.

It implies that data centres need something to get them humming, and any old 'content' will do.

Indifference to the nature of the internet's substance aligns with Marshall McLuhan's insistence on the unimportance of 'content' when considering a medium's impact.

In his best-known work, McLuhan[6] writes:

[...] the personal and social consequences of any medium — that is, of any extension of ourselves — result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.[6:1]

The 'new scale that is introduced into our affairs' by the World Wide Web is its abundant access to media.

The enormous upscaling in data availability means that one of the 'messages' of the internet medium is its superabundant information, rather than anything in particular it carries.

A 'personal and social consequence' of zettabytes of online abundance is the dilution and devaluation of the media they contain. Jon Higgs[7] notes that in an era of scarcity, audio, audiovisual, and written texts were hard-won and ephemeral cultural artefacts:

Those who grew up before the internet understood meaningful culture to be something they had to go out and hunt down. [...] Programmes, films, books and music came and went, and there was no expectation that media would remain easily available long after its initial release. In this context, the good stuff was extremely precious. If you found it, it meant a lot. You certainly would not have described it with a word like 'content'.[7:1]

It may now be easier to access the 'good stuff' online consistently, but that doesn't necessarily mean there's more of it than before. It's now necessary to 'hunt down' substantial nourishment while resisting the urge to gorge yourself on an ample ambient diet of empty calories.

Although inclined to resist, I've often succumbed, spending inadvisable hours scrolling through an indifferent array of pet videos, practical jokes, and road rage incidents on social media. Even when these include clips from work I previously sought — such as favourite films and sitcoms — they fail to provide satisfying entertainment. A longer work would have been more gratifying than fragments that barely qualify as amuse-bouches.

Abundance demands greater discernment than scarcity. This judgment applies as much to creation as to consumption. If you've invested in writing to the extent that McKee[1:2] advocates — taking a decade or more of adult life to master your craft — your goal is to produce work that readers will hunt down.

And writers who strive to create work worth seeking out begin by respecting their writing enough not to reduce it to 'content'.

McKee, R. (1998) Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting. London: Methuen, p. 150. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Burchill, J. (1998) I Knew I Was Right: An Autobiography. London: Heinemann, p. 62. ↩︎ ↩︎

Quote Investigator (2015) Quote Origin: That's Not Writing; That's Just Typing. Available from: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/09/18/typing/#d4112f7a-1750-40de-b0e3-42823f32602e [Accessed 20 July 2025]. ↩︎

Hill, P. (1957) Truman Capote, the Art of Fiction No. 17. The Paris Review [online]. Spring-Summer 1957 (16) [Accessed 21 July 2025]. ↩︎

Orwell, G. (1987) The Complete Novels of George Orwell [online]. Kindle ed. London: Penguin. [Accessed 22 July 2025]. ↩︎ ↩︎

McLuhan, M. (2013) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man [online]. Electronic ed. Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press. [Accessed 12 December 2025]. ↩︎ ↩︎

Higgs, J. (2025) Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story of Doctor Who [online]. Kindle ed. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. [Accessed 08 December 2025]. ↩︎ ↩︎